When AstraZeneca walked into the Oval Office and announced a drug pricing deal, the headlines wrote themselves. Lower prices. Most-favored-nation terms. Billions in U.S. investment.

But here's what those headlines missed.

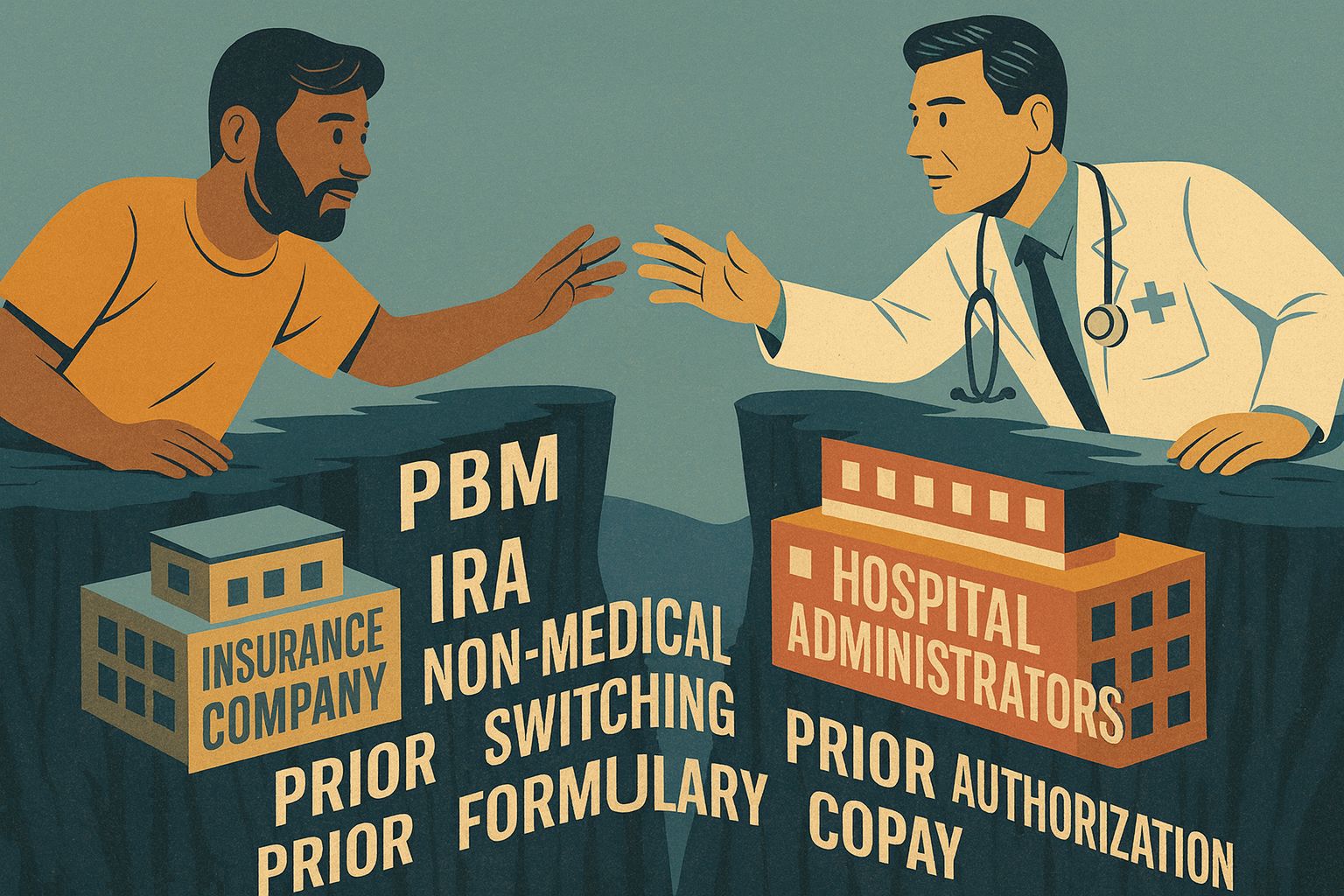

So many issues inhibit the doctor/patient relationship…

These deals don't address a single drug that is currently causing affordability problems.

I've looked at the structure of these most-favored-nation agreements. They focus exclusively on future drug launches. The medications with sky-high prices today? Not included.

That's the easy way out for pharmaceutical companies. They avoid tough conversations about existing products while generating goodwill headlines.

The Two-to-Three Year Wait

Even if these deals work exactly as promised, patients won't see benefits for at least two to three years.

Why? Drug development cycles don't move faster because of an Oval Office photo op.

Meanwhile, today's patients navigate a brutal maze. Prior authorizations. Copay accumulators. Alternative funding programs that force them to seek charity from nonprofits or pharmaceutical companies themselves.

The MFN deals don't change any of that.

Where Your Savings Actually Disappear

Here's the part that matters most. Even when these lower-priced drugs eventually launch, the savings won't reach patients.

They'll vanish at the pharmacy benefit manager.

The PBM system operates on a straightforward principle: higher drug prices result in higher rebates. Research indicates that a $1 increase in rebates is associated with a $1.17 increase in list prices.

This creates a perverse incentive. PBMs don't want lower list prices. They need high prices to generate their revenue.

When GSK tried to launch products at genuinely low list prices, Congressional testimony revealed what happened. The drugs got blackballed. PBMs blocked them from formularies.

Why? Because low-priced drugs don't generate rebates. And rebates are how PBMs make money.

The Monopoly Nobody's Addressing

Here's the structural problem that makes all of this possible.

Three PBMs control nearly 80% of all prescriptions in America. CVS Caremark. Express Scripts. OptumRx.

But it's worse than simple market concentration.

These PBMs are owned by insurance companies that also own healthcare providers. The payer is the PBM. The PBM owns the pharmacy. The insurer owns the clinic.

This vertical integration is fundamentally anticompetitive.

When there's no real competition, there's no market pressure to lower prices for patients. That's evident in the massive increases in premiums and deductibles we've seen.

The Equity Problem Gets Worse

Some pharmaceutical companies are launching direct-to-consumer platforms. "Pharma to table" models allow patients to buy medications outside their insurance at discounted prices.

Sounds promising. But it creates a two-tier system.

Patients who are aware of these programs and can afford the upfront costs gain access. Everyone else doesn't.

The real barriers go deeper than pricing anyway. Many patients are unaware that they can challenge prior authorization denials. They don't know hospitals offer charity care. They face transportation challenges getting to pharmacies or doctors' offices.

This is a social determinant of health issue, not just a pricing issue.

But you won't hear that discussed in Oval Office announcements.

What Would Actually Work

I keep coming back to the same question. If you wanted to genuinely lower drug costs for patients, what would you do?

The answer is structural, not voluntary.

Eliminate rebates from the PBM system entirely. Replace them with flat service fees that aren't tied to drug prices.

That would remove the financial incentive for PBMs to demand higher list prices. It would allow manufacturers to set genuinely lower prices without getting blackballed from formularies.

That's the reform that would help patients.

Positioning Theater

So why are Pfizer and AstraZeneca lining up to make these deals?

They're positioning themselves as cooperative partners before the real fight over PBM reform begins. They're creating goodwill stories while avoiding immediate concessions on their most profitable existing products.

The administration has signaled interest in PBM reform since Trump's first term. With three more years in office, pharmaceutical companies are betting that cooperation now pays off later.

Maybe that calculation proves correct. Maybe we will eventually see meaningful PBM reform.

But right now, today, for patients struggling to afford medications?

We're rearranging deck chairs.

The FTC and federal government have allowed PBM power to grow unchecked. When 80% of patients are governed by three entities, there's no real competition driving prices down.

These voluntary manufacturer agreements sound good in press releases. They might even lead somewhere useful eventually.

But they don't address the structural problem. They don't help patients navigating the system right now. And they don't challenge the monopolistic dynamics that keep drug costs high regardless of manufacturer pricing.

Until we tackle PBM reform directly, we're not solving the affordability crisis.

We're just making it look like we are.

By: Matt Toresco | Founder, CEO & CPO | Archo Advocacy, LLC